Vladimir-Suzdal

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

Grand Principality of Vladimir Великое княжество Владимирское | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1125–1389 | |||||||||

Seal of Alexander Nevsky

| |||||||||

Vladimir-Suzdal in 1237 | |||||||||

| Capital | Suzdal (1125–1157) Vladimir (1157–1389) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Russian | ||||||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodoxy | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Grand Prince | |||||||||

• 1125–1157 (first) | Yuri Dolgoruky | ||||||||

• 1363–1389 (last) | Dmitry Donskoy | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1125 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1389 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Russia | ||||||||

| History of Russia |

|---|

|

|

|

The Principality of Suzdal,[a] from 1157 the Grand Principality of Vladimir,[b] also known as Vladimir-Suzdal,[c] or simply Suzdalia,[1] was a medieval principality that was established during the disintegration of Kievan Rus'. In historiography, the territory of the grand principality and the principalities that emerged from it is commonly denoted as north-east Russia or north-east Rus'.[d][2]

Yury Dolgoruky (r. 1125–1157) moved his capital from Rostov to Suzdal in 1125, following the death of his father.[3] He ruled a principality that had become virtually independent.[4] His son Andrey (r. 1157–1175) moved the capital to Vladimir and had Kiev sacked in 1169, leading to political power shifting to the north-east.[5] Andrey's younger brother Vsevolod III (r. 1176–1212) secured control of the throne, and following his death, a dynastic conflict ensued. Yury II (r. 1212–1216, 1218–1238) was killed during the Mongol invasions of 1237–1238.[6] His younger brother Yaroslav II (r. 1238–1246) and the other princes submitted to Mongol rule.[7]

By the end of the 13th century, the grand principality had fragmented into over a dozen appanages.[8] Moscow and Tver emerged as the two leading principalities, leading to a struggle between them for possession of the grand princely throne.[9] From 1331, the prince of Moscow was also the grand prince of Vladimir, except for one brief interruption from 1359 to 1363, when the throne was held by Nizhny Novgorod.[10] In 1389, the grand principality became a family possession of the prince of Moscow and the two thrones were united.[11] The original territory of the grand principality would later serve as the core of the Russian state.[12]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]The first known prince of Rostov mentioned in the Primary Chronicle under the year 988 was Yaroslav Vladimirovich, appointed by his father Vladimir I of Kiev.[13] In 1024, there was reportedly a famine in the area, and a revolt stoked up by pagan sorcerers was suppressed by Yaroslav personally.[13] Upon his death in 1054, Vsevolod Yaroslavich received the lands of Rostov and Suzdal.[13] Little is known about the region until the 1090s, except that the town of Yaroslavl had been founded upon the upper Volga by 1071, and that Vladimir Monomakh ordered a church to be built in Rostov.[14] Bishops are recorded in the 1080s and 1090s, but the seat appears to have remained vacant for the next half-century.[15] The 1097 Council of Liubech confirmed Vladimir Monomakh's possession of Rostov and Suzdal.[14] By the early 12th century, the towns of Rostov, Suzdal and Murom remained junior postings.[16]

Rostov-Suzdal

[edit]

At the 1097 Council of Liubech, Monomakh became prince of Pereyaslavl, including Rostov, for which he made an appanage for his sons.[14] From that time onwards, the Rostov region was a point of contention between the Monomakhovichi of Pereyaslavl and the Sviatoslavichi of Murom.[17] Control of the upper Volga river was particularly important, as it was the primary route for trade between Volga Bulgaria to the east and Veliky Novgorod to the west.[18] Intercepting that commercial shipping for their own profit was tempting for the Monomakhovichi, but also risky, as it provoked hostilities with both the Bulgars and Novgorodians.[18]

It seems that by the year 1108, Monomakh's sixth son Yuri Dolgorukiy, who resided in the town of Suzdal', was the prince of Rostov.[19] In the same year, he supposedly founded the fortified outpost of Vladimir (Volodimer) on the Klyazma, to control that river and defend against raids of the Volga Bulgars who had attacked in 1107.[17] In 1120, Yuri conducted a military campaign against Bolghar territory.[20]

During the 11th and 12th centuries when southern parts of Rus' were systematically raided by Turkic nomads, their inhabitants began to migrate northward. In the formerly wooded areas, known as Zalesye, many new settlements were established.[citation needed] The foundations of Pereslavl, Kostroma, Dmitrov, Moscow, Yuriev-Polsky, Uglich, Tver, Dubna, and many others were assigned (either by chronicle or popular legend) to G, whose sobriquet ("the Long-Armed") alludes to his dexterity in manipulating the politics of far-away Kiev. Sometime in 1108 Monomakh strengthened and rebuilt the town of Vladimir on the Klyazma River, 31 km south of Suzdal. During the rule of Yuri, the principality gained military strength, and in the Suzdal-Ryazan war of 1146, it conquered the Ryazan Principality. Later in the 1150s, Yuri occupied Kiev a couple of times as well. From that time the lands of the northeastern Rus' played an important role in the politics of Kievan Rus'.[citation needed]

Rise of Vladimir

[edit]Yuri's son Andrey Bogolyubsky significantly increased Vladimir's power at the expense of the nearby princely states, which he treated with contempt.[citation needed] Unwilling to share power with his brothers and cousins, he drove them out and seized all their lands by 1162, thus uniting his father's patrimony in Vladimir-Suzdal under his sole rule (samovlastets).[21] When grand prince Rostislav I of Kiev died in 1167, a succession crisis broke out in which Andrey argued that, according to the emergent tradition of the Principality of Pereyaslavl being the domain of the crown prince of Kiev, his brother Gleb ought to be enthroned.[22] After sacking Kiev in 1169, he enthroned his younger brother. Meanwhile, Andrey embellished Vladimir with white stone churches and monasteries. Gleb's death in 1171 led to yet another succession crisis that saw the Suzdalians kicked out of Kiev; Andrey formed another coalition in an attempt to retake the capital, but was utterly defeated in the Siege of Vyshgorod (1173).[23] The coalition fell apart, and some months later, prince Andrey was murdered by his own boyars in his suburban residence at Bogolyubovo in 1174.[23]

During the 1174–1177 Suzdalian war of succession, Andrey's brother Vsevolod III secured the throne of Vladimir, although the Yurievichi lost control of the Novgorod Republic for a decade.[23] The Yurievichi clan also dropped out of the competition for the Kievan throne, never seeking it again,[24] supporting Rurik Rostislavich's accession in 1194.[25] Instead, Vsevolod's chief focus was on subjugating the southern Ryazan Principality, which appeared to stir discord in the princely family, and the mighty Turkic state of Volga Bulgaria, which bordered Vladimir-Suzdal to the east. After several military campaigns, Ryazan was burnt to the ground in 1208, and the Bulgars were forced to pay tribute.[citation needed]

Fragmentation

[edit]

Vsevolod's death in 1212 precipitated another serious dynastic conflict. His eldest son Konstantin gained the support of powerful Rostovan boyars and Mstislav the Bold of Kiev and expelled the lawful heir, his brother George, from Vladimir to Rostov. George managed to return to the capital six years later, upon Konstantin's death. George proved to be a shrewd ruler who decisively defeated Volga Bulgaria and installed his brother Yaroslav in Novgorod. His reign, however, ended when the Mongol hordes under Batu Khan took and burnt Vladimir in 1238. Thereupon they proceeded to devastate other major cities of Vladimir-Suzdal during the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus'.[citation needed]

Under Mongol suzerainty

[edit]

While heavy tribute payments and the initial Mongol invasions did manage to cause much destruction to Vladimir-Suzdal, rule under the Mongols also brought wealth to the region, as Vladimir was able to access the Mongol's lucrative patronage of oriental trade.[26]

None of the cities of the principality managed to regain the power of Kievan Rus' after the Mongol invasion. Vladimir became a vassal of the Mongol Empire, later succeeded by the Golden Horde, with the Grand Prince appointed by the Great Khan. Even the popular Alexander Nevsky of Pereslavl had to go to the Khan's capital in Karakorum to be installed as the Grand Prince in Vladimir. As many factions strove for power, the principality rapidly disintegrated into eleven tiny states: Moscow, Tver, Pereslavl, Rostov, Yaroslavl, Uglich, Belozersk, Kostroma, Nizhny Novgorod, Starodub-upon-Klyazma, and Yuriev-Polsky. All of them nominally acknowledged the suzerainty of the Grand Prince of Vladimir, but his effective authority became progressively weaker.[citation needed]

By the end of the century, only three cities — Moscow, Tver, and Nizhny Novgorod — still contended for the title of Grand Prince of Vladimir. Once installed, however, they chose to remain in their own cities rather than move to Vladimir. The Principality of Moscow gradually came to eclipse its rivals. The decision of metropolitan Peter of Kiev and all Rus' to move his chair from Vladimir to Moscow in 1325 was another sign of Moscow's rising prominence.[citation needed] When the Tver Uprising of 1327 broke out, the Muscovites and Nizhegorodians helped the Mongols crush it.[citation needed] By the end of the 1330s, Moscow had eclipsed Tver, which then descended inter-princely wars between the various appanages of Tver, particularly between Kashin and Mikulin.[27] During the Great Troubles, Tver and Nizhny Novgorod-Suzdal both attempted to regain the title of grand prince of Vladimir, with Tver succeeding a few times, but since 1394, Moscow effectively inherited the title and controlled Vladimir thereafter, signifying the end of a separate Vladimirian principality.

Culture

[edit]Suzdalian period

[edit]

As part of the Christian world, Rus' principalities gained a wide range of opportunities for developing their political and cultural ties not only with Byzantium but with the European countries, as well. By the end of the eleventh century, Rus' gradually fell under the influence of Roman architecture. Whitestone cathedrals, decorated with sculpture, appeared in the principality of Vladimir-Suzdal due to Andrey Bogolyubsky's invitation of architects from "all over the world". These cathedrals, however, are not identical to the Roman edifices of Catholic Europe and represent a synthesis of the Byzantine cruciform plan and cupolas with Roman whitestone construction and decorative technique. This mixture of Greek and Western European traditions was possible only in Kievan Rus'. One of its results was a famous architectural masterpiece of Vladimir, the Church of Pokrova na Nerli, a symbol of cultural originality of Suzdalia.[citation needed]

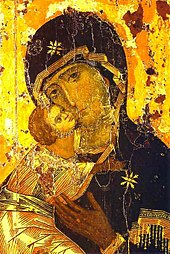

In the early Middle Ages, Rus' principalities were similar to other European countries culturally and in historical development. Later on, however, the Rus' polities and Europe began diverging due to a number of factors. The East-West Schism of 1054 was one of the reasons for this. Barely noticeable in the eleventh century, it became very obvious two centuries later during the resistance of the citizens of Novgorod to the Teutonic Knights. Also, by the middle of the twelfth century, the dominating influence of the Kievan Rus’ (some historians do not consider it possible to even call it a state in the modern sense of the word) began to wane. The famous Theotokos of Vladimir, an icon of the Virgin Mary, was moved to Vladimir. From this time on, almost every principality began forming its own architectural and art schools.[citation needed]

The invasion of Batu Khan and subsequent domination of Rus' lands by the Golden Horde was also a turning point in the history of Russian culture and statehood. Mongol rule imposed its principles of state on the northeastern Rus' principalities, which were very different from those of Western Europe. In particular, Russia adopted a principle of universal subordination and undivided authority.[citation needed]

Muscovite period

[edit]Rus' was only able to recover from the consequences of the Mongol invasion by the late thirteenth century. The first areas to recover were Novgorod and Pskov, which had been spared the Tatar raids. These city-states, with parliamentarian rule, created an original kind of culture under some influence from their western Baltic neighbours. In the early fourteenth century, leadership in the northeastern lands was transferred from the Principality of Vladimir to Moscow, which, in turn, would fight for leadership against Tver for another century. Moscow was a part of the Vladimir lands and functioned as one of the border fortresses of north-eastern Rus'. In 1324, Metropolitan Peter left Vladimir and settled down in Moscow, thus, transferring the residence of the Russian Orthodox Church (Metropolitan Maximus had moved the residence from Kiev to Vladimir not long before, in 1299). In the late fourteenth century, the principal object of worship of the "old" capital—the icon of the Theotokos of Vladimir—was transferred to Moscow. Vladimir became a model for Muscovy.[citation needed]

Emphasizing the succession, Muscovite princes took good care of Vladimir's sacred places. In the early fifteenth century, Andrei Rublev and Prokhor of Gorodets painted the Assumption (Uspensky) Cathedral. In the mid-1450s, they restored the Cathedral of St. George in Yuriev-Polsky under the supervision of Vasili Dmitriyevich Yermolin.[28] The architecture of Muscovy and its surrounding lands in the fourteenth to early fifteenth centuries, usually referred to as early Muscovite architecture, inherited the technique of whitestone construction and typology of four-pillar cathedrals from Vladimir. Art historians, however, notice that early Muscovite architecture was influenced by the Balkans and European Gothic architecture.[citation needed]

Russian painting of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries is characterized by two major influences, namely those of Byzantine artist Feofan Grek and Russian icon-painter Andrei Rublev.[29] Feofan's style is distinguished by its monochromatic palette and uncommon expressiveness of laconic blots and lines, which send a message of a complex symbolic implication, close to the then widely-spread doctrine of hesychasm, from Byzantium. The soft-coloured icons of Rublev are closer to the late Byzantine painting style of the Balkan countries in the fifteenth century.[citation needed]

The late fourteenth century was marked by one of the most important events in Russian history. In 1380, Dmitry Donskoy and his army dealt the first serious blow to the Golden Horde. Sergii Radonezhsky, the founder and hegumen of Troitse-Sergiyev monastery, played an exceptional role in this victory. The name of Saint Sergii, who became the protector and patron of Muscovy, has an enormous significance in Russian culture. Radonezhsky himself and his followers founded more than two hundred monasteries, which would become the basis for the so-called "monastic colonization" of the little-developed northern lands. The Life of Sergii Radonezhsky was written by one of the outstanding writers of that time, Epifaniy the Wise. Andrei Rublev painted his Trinity, the greatest masterpiece of the Russian Middle Ages, for the cathedral of Sergii's monastery.[citation needed]

Mid-fifteenth-century Muscovy is known for bloody internecine wars for the Moscow seat of the Grand Prince. Ivan III managed to unite the Rus' lands around Moscow (at the cost of ravaging Novgorod and Pskov) only by the end of the fifteenth century, and put an end to Russia's subordination to the Golden Horde after the Great standing on the Ugra river of 1480. The river was later poetically dubbed the "Virgin Belt" (Poyas Bogoroditsy). This event marked the birth of the sovereign Russian state, headed by the Grand Prince of Moscow.[citation needed]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Russian: Суздальское княжество, romanized: Suzdalskoye knyazhestvo.

- ^ Russian: Великое княжество Владимирское, romanized: Velikoye knyazhestvo Vladimirskoye.

- ^ Russian: Владимиро-Суздальское княжество, romanized: Vladimiro-Suzdalskoye knyazhestvo.

- ^ Russian: Северо-Восточная Русь, romanized: Severo-Vostochnaya Rus.

References

[edit]- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 2, "The agriculturally rich 'land beyond the forests' {Zalesskaya zemlya) or Suzdalia, as it is convenient to call the federation of principalities in north-east Russia ruled by Vsevolod III and his numerous sons...".

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 12, "...north-east Russia — the lands of Suzdal' and Vladimir..."; Fennell 2023, p. 11; Dmytryshyn 1977, p. 99, "...northeast Rus was the region of Vladimir-Suzdal...".

- ^ Feldbrugge 2017, p. 33; Venning 2023, 'Grand Principality' of Vladimir-Suzdal.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 3, "By the time of his death in 1125 Suzdalia was virtually independent of Kiev under its sovereign ruler Yury".

- ^ Riasanovsky & Steinberg 2019, p. 67; Fennell 2014, p. 6; Channon & Hudson 1995, p. 16.

- ^ Riasanovsky & Steinberg 2019, p. 68; Fennell 2014, p. 50, "Yury assumed the grand principality once again and installed himself in Vladimir, where he was to remain until his death at the battle on the Sit' river in 1238".

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 99.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 163, "By the end of the thirteenth century the disintegration of Suzdalia was well under way with more than a dozen principalities virtually separated from Vladimir, their rulers out of the running for the grand-princely throne...".

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 151, "Tver' and Moscow were emerging in the last decade of the thirteenth century as the true centres of power in north-east Russia..."; Fennell 2023, p. 11; Crummey 2014, pp. 34, 36.

- ^ Crummey 2014, p. 45; Crummey 2014, p. 40, "During his reign, Ivan I also established that the princes of Moscow had first claim on the grand princely throne. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that, after him, his heirs retained the title and office almost without interruption".

- ^ Fennell 2023, p. 306, "But the most vivid proof of the assimilation of the thrones of Vladimir and Moscow is to be found in Dmitry Donskoy's will of 1389 in which he bequeaths Vladimir to his eldest son".

- ^ Crummey 2014, pp. 36, 212; Feldbrugge 2017, p. 33; Cherniavsky 2017, p. 403, "Completely within the area conquered by the Tatars or Mongols was northeast Russia, the foundation of the later Muscovite tsardom and of Imperial Russia".

- ^ a b c Martin 2007, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Martin 2007, p. 42–43.

- ^ Franklin & Shepard 2014, p. 228.

- ^ Franklin & Shepard 2014, p. 267.

- ^ a b Martin 2007, p. 43, 62.

- ^ a b Martin 2007, p. 77.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 43.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 62.

- ^ Raffensperger & Ostrowski 2023, p. 82.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 124.

- ^ a b c Martin 2007, p. 128.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 130.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 131.

- ^ Halperin, Charles J. (1985). Russia and the Golden Horde: the Mongol impact on medieval Russian history. Internet Archive. Bloomington : Indiana University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-253-35033-6.

- ^ Martin 2007, pp. 210, 231–232.

- ^ Воронин, Н. Н. (1974). Владимир, Боголюбово, Суздаль, Юрьев-Польской. Книга-спутник по древним городам Владимирской земли. (in Russian) (4th ed.). Moscow: Искусство. pp. 262–290. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ^ Lincoln, W. Bruce (1998). Between Heaven and Hell: The Story of a Thousand Years of Artistic Life in Russia. Viking. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-670-87568-9.

Bibliography

[edit]- William Craft Brumfield. A History of Russian Architecture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993) ISBN 978-0-521-40333-7 (Chapter Three: "Vladimir and Suzdal Before the Mongol Invasion")

- Channon, John; Hudson, Robert (1995). The Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-051326-4.

- Cherniavsky, Michael (15 May 2017). "Khan or Basileus: An Aspect of Russian Medieval Political Theory". In Shepard, Jonathan (ed.). The Expansion of Orthodox Europe: Byzantium, the Balkans and Russia. Routledge. pp. 403–420. ISBN 978-1-351-89005-2.

- Crummey, Robert O. (6 June 2014). The Formation of Muscovy 1300 - 1613. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87200-9.

- Dmytryshyn, Basil (1977). A history of Russia. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0133921342.

- Feldbrugge, Ferdinand J. M. (2 October 2017). A History of Russian Law: From Ancient Times to the Council Code (Ulozhenie) of Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich of 1649. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-35214-8.

- Fennell, John (13 October 2014). The Crisis of Medieval Russia 1200-1304. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87314-3.

- Fennell, John (15 November 2023). The Emergence of Moscow, 1304–1359. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-34759-5.

- Franklin, Simon; Shepard, Jonathan (6 June 2014). The Emergence of Rus 750-1200. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87224-5.

- Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia: 980–1584. Second Edition. E-book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-36800-4.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas V.; Steinberg, Mark D. (2019). A history of Russia (Ninth ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190645588.

- Venning, Timothy (30 June 2023). A Compendium of Medieval World Sovereigns. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-86633-9.

- Raffensperger, Christian; Ostrowski, Donald (2023). The Ruling Families of Rus: Clan, Family and Kingdom. London: Reaktion Books. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-78914-745-2. (e-book)