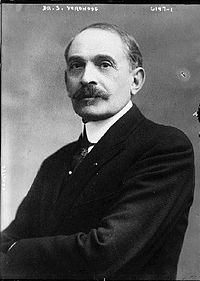

Serge Voronoff

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

Serge Voronoff | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. July 10, 1866 Shekhman, Tambov Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | September 3, 1951 (aged 85) Lausanne, Switzerland |

| Citizenship | Russia, France |

| Known for | Multi-species tissue transplants |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Surgery |

| Institutions | Collège de France |

| Doctoral advisor | Alexis Carrel |

Serge Abrahamovitch Voronoff (Russian: Сергей Абрамович Воронов; c. July 10, 1866 – September 3, 1951) was a French surgeon of Russian origin who gained fame for his practice of xenotransplantation of monkey testicle tissues onto the testicles of men, purportedly as an anti-aging therapy while working in France in the 1920s and 1930s.

His practices made him significantly wealthier. However, his theories remained controversial throughout his life, and he was often ridiculed by medical professionals over his claims. According to one contemporary newspaper, he was famously known as the "monkey gland man."[1] Ultimately almost all his works were later proven false.

Personal life

[edit]Serge (Samuel) Voronoff was born to a Jewish family in the village Shekhman, Tambov Governorate in Russia (now Tambov Oblast) shortly before July 10, 1866, the date of his circumcision in a synagogue. His father Abram Veniaminovich Voronov was a former cantonist[2] and a distiller;[3] his mother was Rachel-Esther Lipsky.[4][5][6] At the age of 18, after graduating from the Voronezh Realschule, he emigrated to France, where he studied medicine. In 1895 at the age of 29, Voronoff became a naturalized French citizen. Voronoff was a student of French surgeon, biologist, eugenicist, and Nobel Prize recipient Alexis Carrel, from whom he learnt surgical techniques of transplantation. Between 1896 and 1910, he worked in Egypt, studying the retarding effects that castration had on eunuchs, observations that would lead to his later work on rejuvenation.

Voronoff married his first wife, Marguerite Barbe, in 1897. She died in 1910. He married his second wife, Evelyn Bostwick, in 1920 (Bostwick's daughter from a previous marriage was Marion "Joe" Carstairs). Bostwick translated Voronoff's book, Life: a means of restoring vital energy and prolonging life, into English. She died on March 3, 1921, at the age of 48. Her legacy gave Voronoff a large income for the rest of his life.[7]

Ten years later, Voronoff married Gerti Schwartz, believed by some to be the illegitimate daughter of King Carol of Romania.[8] She outlived him and became the Condesa da Foz upon Voronoff's death.

Death and burial

[edit]Voronoff died on September 3, 1951, in Lausanne, Switzerland, from complications following a fall.[9] While recovering from a broken leg, Voronoff suffered chest difficulties, thought either to be pneumonia or possibly a blood clot from his leg that moved to his lungs.[9]

Few newspapers ran obituaries, and some of those that did acted as if Voronoff had always been ridiculed for his beliefs. For example, The New York Times, once one of his supporters, spelt his name incorrectly and stated that "few took his claims seriously".[9] On the other hand, TimesDaily was more positive, calling him a "famed prononent proponent of rejuvenation for humans through monkey glands" and claiming that he actually became more popular later in life: "Medical authorities at first rejected his theories, but later developments confirmed some of his ideas."[1]

Voronoff is buried in the Russian section of the Caucade Cemetery in Nice.

Monkey-gland transplant work

[edit]

In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, trends in xenotransplantation included the work of Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard.[10][11] In 1889, Brown-Séquard injected himself under the skin with extracts from ground-up dog and guinea pig testicles. These experiments failed to produce the desired results of increased hormonal effects to retard aging.

Voronoff's experiments launched from this starting point. He believed glandular transplants would produce more sustained effects than mere injections. Voronoff's early experiments in this field included transplanting thyroid glands from chimpanzees to humans with thyroid deficiencies. He moved on to transplanting the testicles of executed criminals into millionaires, but, when demand outstripped supply, he turned to using monkey testicle tissue instead.[12]

In 1917, Voronoff began being funded by Evelyn Bostwick, a wealthy American socialite and the daughter of Jabez Bostwick.[13] The money allowed him to begin transplantation experiments on animals. Bostwick also acted as his laboratory assistant at the Collège de France in Paris, and consequently became the first woman admitted to that institution.[14] They married in 1920.

Between 1917 and 1926, Voronoff carried out over five hundred transplantations on sheep and goats, and also on a bull, grafting testicles from younger animals to older ones. Voronoff's observations indicated that the transplantations caused the older animals to regain the vigor of younger animals.[15] He also considered monkey-gland transplantation an effective treatment to counter senility.[16]

His first official transplantation of a monkey gland into a human took place on June 12, 1920.[17] Thin slices (a few millimetres wide) of testicles from chimpanzees and baboons were implanted inside the patient's scrotum, the thinness of the tissue samples allowing the foreign tissue to fuse with the human tissue eventually.[17] By 1923, 700 of the world's leading surgeons at the International Congress of Surgeons in London, England, applauded the success of Voronoff's work in the "rejuvenation" of old men.[18]

In his book Rejuvenation by Grafting (1925),[19] Voronoff describes what he believes are some of the potential effects of his surgery. While "not an aphrodisiac", he admits the sex drive may be improved. Other possible effects include better memory, the ability to work longer hours, the potential for no longer needing glasses (due to improvement of muscles around the eye), and the prolonging of life. Voronoff also speculates that the grafting surgery might be beneficial to people with "dementia praecox", the mental illness known today as schizophrenia.

Voronoff's monkey-gland treatment was in vogue in the 1920s.[21][22] The poet E. E. Cummings sang of a "famous doctor who inserts monkeyglands in millionaires", and Chicago surgeon Max Thorek, for whom the Thorek Hospital and Medical Center is named, recalled that soon, "fashionable dinner parties and cracker barrel confabs, as well as sedate gatherings of the medical élite, were alive with the whisper - 'Monkey Glands'."[23]

By the early 1930s, over 500 men had been treated in France by his rejuvenation technique (including Voronoff's younger brother Georges[24]), and thousands more around the world, such as in a special clinic set up in Algiers.[25] Noteworthy people who had the surgery included Harold McCormick, chairman of the board of International Harvester Company.[26][27][28] To cope with the demand for the operation, Voronoff set up his own monkey farm in Ventimiglia, on the Italian Riviera, employing a former circus-animal keeper to run it.[23] French-born U.S. coloratura soprano Lily Pons was a frequent visitor to the farm.[29] With his growing wealth, Voronoff occupied the whole of the first floor of one of Paris's most expensive hotels, surrounded by a retinue of chauffeurs, valets, personal secretaries and two mistresses.[30]

Voronoff's later work included transplants of monkey ovaries into women. He also tried the reverse experiment, transplanting a human ovary into a female monkey, and then tried to inseminate the monkey with human sperm. The notoriety of this experiment resulted in the novel Nora, la guenon devenue femme (Nora, the Monkey Turned Woman) by Félicien Champsaur. In 1934, he was the first to officially recognise scientific work done by Greek Professor Skevos Zervos.

Falling out of favour

[edit]Voronoff's experiments ended following pressure from a sceptical scientific community and a change in public opinion.[31] It became clear that Voronoff's operations did not produce any of the results he claimed.

In his book The Monkey Gland Affair, David Hamilton, an experienced transplant surgeon, discusses how animal tissue inserted into a human would not be absorbed, but instantly rejected. At best, it would result in scar tissue, which might fool a person into believing the graft is still in place. This means the many patients who received the surgery and praised Voronoff were "improved" solely by the placebo effect.

Part of the basis of Voronoff's work was that testicles are glands, much like the thyroid and adrenal glands. Voronoff believed that at some point, scientists would discover what substance the testicular glands secrete, making grafting surgery unnecessary.

Eventually, it was determined that the substance emitted by the testicles is testosterone. Voronoff expected that this new discovery would prove his theories. Testosterone would be injected into animals and they would grow young, strong, and virile. Experiments were performed, and this was not the case. Besides an increase in some secondary sexual characteristics, testosterone injections did little. Testosterone did not prolong life, as Voronoff expected. In the 1940s, Kenneth Walker, an eminent British surgeon, dismissed Voronoff's treatment as "no better than the methods of witches and magicians."[32]

In the 1940s, his treatment was widely used by football players at Wolverhampton Wanderers and Portsmouth, although it eventually fell out of favour.[33]

Reputation and legacy

[edit]By 1935, rejuvenation operations on testes were obsolete.[34] Kozminski and Bloom (2012) wrote that Voronoff's experiments were "plagued by secrecy, subjectivity and sensationalism", adding that the era of testosterone surgery was ended by a "lack of verifiable data".[34] They write that Voronoff and others can be faulted for "paternalistic use of patients and misogynistic message of testicular power", but that efforts such as these in the history of urology may have helped fuel medical progress.[34] They conclude that "the boundary between legitimate practice … and the self-interest of chicanery must be abrogated" with medical and regulatory vigilance.[34]

Haber (2004) stated that "Despite increasing doubts about the efficacy of his operation, he continued to perform both human and animal operations to popular acclaim."[35] In 2005, Kahn stated that the work by Voronoff and others in the 1920s and 1930s therapies that "received widespread [...] ridicule in the popular press, were spread rapidly by practitioners of questionable training and ethical motivation, and finally and relatively quickly disappeared from common use".[36]

Popular culture

[edit]As Voronoff's work became famous in the 1920s, it began to be featured in popular culture. By 1994, there were calls for a qualified apology from the orthodox medical establishment for dismissing Voronoff's work.[30] In 1998, the sweeping popularity of Viagra brought forth references to Voronoff in the popular press.[32][37] By 2003, Voronoff's efforts in the 1920s reached trivia factoid status for newspapers.[38]

"The Adventure of the Creeping Man" is a Sherlock Holmes short story by Arthur Conan Doyle, first published in March 1923 but set in 1903. In the story, an elderly professor is found to be regularity injecting himself with a substance called "extract of langur" for the purpose of rejuvenation. This has unexpected consequences for him.

The song "Monkey-Doodle-Doo", written by Irving Berlin and featured in the Marx Brothers film The Coconuts, contains the line: "If you're too old for dancing/Get yourself a monkey gland". Strange-looking ashtrays depicting monkeys protecting their private parts, with the phrase (translated from French) "No, Voronoff, you won't get me!" painted on them began showing up in Parisian homes.[39] At about this same time, a new cocktail containing gin, orange juice, grenadine and absinthe was named The Monkey Gland.[40]

Voronoff was the prototype for Professor Preobrazhensky in Mikhail Bulgakov's novel Heart of a Dog, published in 1925.[41] In the novel, Preobrazhensky implants human testicles and pituitary gland into a stray dog named Sharik. Sharik then proceeds to become more and more human as time passes, picks himself the name Polygraph Polygraphovich Sharikov, makes himself a career with the "department of the clearing of the city from cats and other vile animals", and turns the life in the professor's house into a nightmare until the professor reverses the procedure.

In his autobiography A Chef's Tale, Pierre Franey relates how when Voronoff dined at Le Pavillon in the 1940s, waiters would remark how "he looked like a monkey himself, with his exceptionally long fingers and slouching walk. They would laugh at him in the kitchen and imitate his walk for those of us (in the kitchen) who couldn't witness it ourselves."[42]

Works by Voronoff

[edit]- Voronoff, Samuel. (1893) Essai sur les trèves morbides. Paris: A. Maloine.

- Voronoff, Samuel (transl.). (1895) S. Bernheim et É. Laurent. Hystérie. Paris: A. Maloine.

- Voronoff, Samuel. (1896) Études de gynécologie et de chirurgie générale. Paris: A. Maloine.

- Voronoff, Samuel. (1899) Manuel pratique d'opérations gynécologiques. Paris: O. Doin.

- Voronoff, Samuel. (1910) Feuillets de chirurgie et de gynécologie. Paris: O. Doin et fils.

- Voronoff, Serge. (1920) Life: A Study of the Means of Restoring. Publisher: E. P. Dutton & Company, New York. ASIN B000MX31EC

- Voronoff, Serge. (1923) Greffes Testiculaires. Publisher: Librairie Octave Doin. ASIN B000JOOIA0

- Voronoff, Serge. (1924) Quarante-Trois Greffes Du Singe a L'homme. Publisher: Doin Octave. ASIN B000HZVQUQ

- Voronoff, Serge. (1925) Rejuvenation by grafting. Publisher: Adelphi. Translation edited by Fred. F. Imianitoff. ASIN B000OSQH5K

- Voronoff, Serge. (1926) Etude sur la Vieillesse et la Rajeunissement par la Greffe. Publisher: Arodan, Colombes, France. ASIN B000MWZJHU

- Voronoff, Serge. (1926) The study of old age and my method of rejuvenation. Publisher: Gill Pub. Co. ASIN B000873F7A

- Voronoff, Serge. (1928) How to restore youth and live longer. Publisher: Falstaff Press. ASIN B000881RLU

- Voronoff, Serge. (1928) The conquest of life. Publisher: Brentano's. ASIN B000862P0E

- Voronoff, Serge. (1930) Testicular grafting from ape to man: Operative technique, physiological manifestations, histological evolutions, statistics. Publisher: Brentano's. ASIN B00088JAL4

- Voronoff, Serge. (1933) Les sources de la vie. Publisher: Fasquelle editeur. ASIN B000K5XTTO

- Voronoff, Serge. (1933) The Conquest of Life. Publisher: Brentano's. ASIN B000862P0E

- Voronoff, Serge. (1937) Love and thought in animals and men. Publisher: Methuen. ASIN B000HH293C

- Voronoff, Serge. (1941) From Cretin to Genius. Publisher: Alliance. ASIN B000FX4UP8

- Voronoff, Serge. (1943) The Sources of Life. Publisher: Boston, Bruce Humphries. ASIN B000NV3MZ6

Notes and references

[edit]- Citations

- ^ a b Monkey Gland Man Dies, Buried Italy, TimesDaily

- ^ Voronoff Called to Turkey to Improve Breed of Sheep Through Gland Grafting (Jewish Telegraph Agency)

- ^ Badenoch AW (1986). "Autumn Books: "Youth's a stuff will not endure"". Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 293 (6553): 1005–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6553.1005. PMC 1341788. PMID 20742714.

- ^ Marguerite BARBE et Samuel Serge VORONOFF

- ^ The Voronoff Family

- ^ Arrêté du 24 octobre 2001 portant apposition de la mention « Mort en déportation» sur les actes et jugements déclaratifs de décès (Voronoff's brothers Alexandre and Georges)

- ^ Summerscale 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Summerscale 1998, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Hamilton, David. (1986) The Monkey Gland Affair. Publisher: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-3021-0

- ^ Musitelli, S. (June 1, 2004) The Aging Male Welcome born-again Dr Faust! Volume 7; Issue 2; Page 170.

- ^ Bynum, W. F. (June 30, 2006) The Times Higher Education Supplement Dig for gland of hope and glory;Books;History of science. Section: Features; Page 29.

- ^ Winegar, Karin. (February 5, 1989) Star Tribune Youth is a disease that time cures. - Goethe. Section: Variety; Page 01E.

- ^ Summerscale 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Summerscale 1998, p. 29.

- ^ "New glands for old". Lancet. 338 (8779): 1367. 1991. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(91)92244-V. PMID 1682744. S2CID 27782721.

- ^ Sengoopta Chandak (1993). "Rejuvenation and the prolongation of life: science or quackery?" (PDF). Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 37 (1): 55. doi:10.1353/pbm.1994.0024. S2CID 72825826.

- ^ a b Gillyboeuf, Thierry. (October 2000) The Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society. The Famous Doctor Who Inserts Monkeyglands in Millionaires. Archived 2006-11-11 at the Wayback Machine Pg. 44-45.

- ^ Time magazine (July 30, 1923) Voronoff and Steinach.

- ^ Voronoff, Serge. (1925) Rejuvenation by grafting. Publisher: Adelphi. Translation edited by Fred. F. Imianitoff. ASIN B000OSQH5K

- ^ Voronoff, Serge (1920). Life. Dutton. pp. 99.

- ^ Ferris, Paul. (December 2, 1973) The New York Times The history of cell therapy and its use in modern clinics.

- ^ Klotzko, Arlene Judith. (May 21, 2004) Financial Times Science matters. Section: FT Weekend Magazine - Of All Things.

- ^ a b Sengoopta, Chandak. (August 1, 2006) History Today Secrets of Ethernal Youth. Volume 56; Issue 8; Page 50. (A review of how the discovery of hormones, the body's chemical messengers, revolutionized ideas of human nature and human potential in the twentieth century.)

- ^ Georges Voronoff (1873—1943)

- ^ Common, Laura. (April 25, 2000) The Medical Post [1] Great balls of fire: from prehistory, men have tried implants and extracts from macho animals to cure impotence, but it was only relatively recently that they began to understand why they did so.

- ^ Grossman, Ron. (March 31, 1985) Chicago Tribune Lost lake shore drive: Mourning an era; Mansions of rich and famous yield to giant condos. Section: Real estate; Page 1.

- ^ Jones, David. (December 11, 1986) The Times Christmas Books: Believe it or not - Adam and Eve to bent spoons / Review of books on beliefs.

- ^ "France: Chimpanzee Present?". Time. 16 April 1928. Archived from the original on May 16, 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ A Time article from 1940 says Lily Pons: "was kissed by an ape at Dr. Voronoff's monkey farm near Menton, France". Another Time article, this time from 1936, says "Singer Lily Pons went to see the monkeys kept by Menton's famed Rejuvenating Dr. Serge Voronoff, got too close to a cage, was soundly bussed by an ape named Rastus."

- ^ a b Le Fanu, James (January 6, 1994) The Times The monkey gland secret. Section: Features; Page 15.

- ^ Illman, John. (August 4, 1998) Rocky Mountain News Pre-viagra men given monkey cells in the 1930s, Russian doctor grafted glands. Section: News/National/International; Page 26A. (from The Observer

- ^ a b The Cincinnati-Kentucky Post (November 5, 1998) Medical monkey business. Section:News; Page 22A

- ^ Norrish, Mike (2009-04-22). "Andrei Arshavin's feat throws spotlight on ultimate case of monkey business". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2009-04-25. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- ^ a b c d Kozminski MA, Bloom DA (March 2012). "A brief history of rejuvenation operations". J. Urol. (Review). 187 (3): 1130–4. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.134. PMID 22266009.

- ^ Haber C (June 2004). "Life extension and history: the continual search for the fountain of youth". J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 59 (6): B515–22. doi:10.1093/gerona/59.6.b515. PMID 15215256.

- ^ Kahn A (February 2005). "Regaining lost youth: the controversial and colorful beginnings of hormone replacement therapy in aging". J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 60 (2): 142–7. doi:10.1093/gerona/60.2.142. PMID 15814854.

- ^ Campbell-Johnston, Rachel. (August 5, 1998) The Times The price of priapic paradise. Section: Features; Page 16.

- ^ mX (February 27, 2003) It's true. Section: News; Page 7. (printing, "Russian transplant pioneer Serge Voronoff made headlines in 1920 by grafting monkey testicles onto human males.")

- ^ Nugent, Karen. (April 9, 2000) Telegram & Gazette "Xeno-grafting" explored \ Clinton doctor writes the book. Section: Local news; Page B1.

- ^ Hirst, Christopher. (October 8, 2005) The Independent 101 cocktails that shook the world #37: The Monkey Gland. Section: Features; Page 57.

- ^ Tatiana Bateneva. In the quest for longevity humans are ready to become relatives with any animals (in Russian)

- ^ Franey, Pierre (1994) A Chef's Tale: A Memoir of Food, France, and America. Alfred A. Knopf: New York. Page 94.

- Bibliography

- Cooper, David K. C.; Lanza, Robert P. (April 28, 2003) Xeno: The Promise of Transplanting Animal Organs into Humans. Publisher: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-512833-8

- Hamilton, David. (1986) The Monkey Gland Affair. Publisher: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-3021-0

- Réal, Jean. (2001) Voronoff. Publisher: Stock. ISBN 2-234-05336-6

- Summerscale, Kate (1998). The Queen of Whale Cay. Fourth Estate. ISBN 1-85702-668-3.

- Enzo Barnabà, Il sogno dell'eterna giovinezza, Formigine, Infinito, 2014. (ISBN 9788868610388).

See also

[edit]- Cosmic Movement

- Eugen Steinach

- Brown-Séquard Elixir At age 72, at a meeting of the Societie de Biologie in Paris in 1889, Brown-Séquard reported that hypodermic injection of a fluid prepared from the testicles of guinea pigs and dogs leads to rejuvenation

- Monkeygland sauce

- The Monkey Gland

- John R. Brinkley